Mister Crump Don’t Like It

“There were things that were almost dangerous to say, but you could sing it.”

Trigger warning: here’s some United States history. It’s a deep drift into the Before Elvis universe that shares certain odd coincidences with our present circumstance.

A machine boss of the last century named E.H. Crump presided over one of the most ruthless, effective political organizations of all time. He also, however inadvertently, inspired a renaissance of American music that has vastly exceeded his political machine in its impact and legacy. For nearly fifty years, Crump ran the city of Memphis, its surrounding county, the state of Tennessee, and that state’s federal participation, controlling seats in the U.S. Congress, Senate, and its electoral votes. But because of him and in spite of him, the city’s culture flourished. Boss Crump ruled from the birth of the blues to the birth of rock ’n’ roll.

Crump’s rise is bound inextricably to the first major hit of the blues genre, W.C. Handy’s “Mr. Crump” aka “Memphis Blues.”

Crump, or more likely Crump’s supporters, one of whom ran a popular saloon, hired Handy, at his own word just the third most popular bandleader on Beale Street, to perform on behalf of the Crump campaign, drawing crowds to the candidate’s events.

For Crump’s theme, Handy pieced together an instrumental from various street sources he’d heard, a slide guitarist on a train platform in Tutwiler, Mississippi, a string band in Cleveland, Mississippi, and piano thumpers in Memphis joints. When Handy and his band played the song, people got moving. But not necessarily for Crump.

Crump claimed that he would end vice in the city, a campaign promise like most others, and in the Beale Street saloons Handy heard partiers say that they didn’t care what Crump wouldn’t allow, they’d just barrelhouse anyhow, “Mr. Crump can go and catch his self some air.”

In reality, Crump had his own support among saloonkeepers, who sought to curry his favor so that they could continue their illegal operations after his election. One of these, Jim Mulcahy, sometimes employed W.C. Handy at the Blue Heaven, a place for raw whiskey, cockfights, and early blues.

Handy credits one of his bandmen with first singing the verse, Mr. Crump won’t allow no easy riders here, easy rider being the term for a pimp back then, Mr. Crump won’t allow no easy riders here. We don’t care what Mr. Crump won’t allow, we gon’ barrelhouse anyhow, Mr. Crump can go and catch his self some air.

To Handy the lines felt too dangerous to say or to sing, so he kept to the instrumental version in public.

Crump meanwhile accused his opponent in the election of herding undocumented Black voters from low dives to the polls (anyone appearing with a poll tax receipt could cast a ballot in this era before photo ID) much as his phonetic descendent accused his opposition of voting undocumented immigrants. It worked (x2). Crump took over the Memphis mayoralty in 1910.

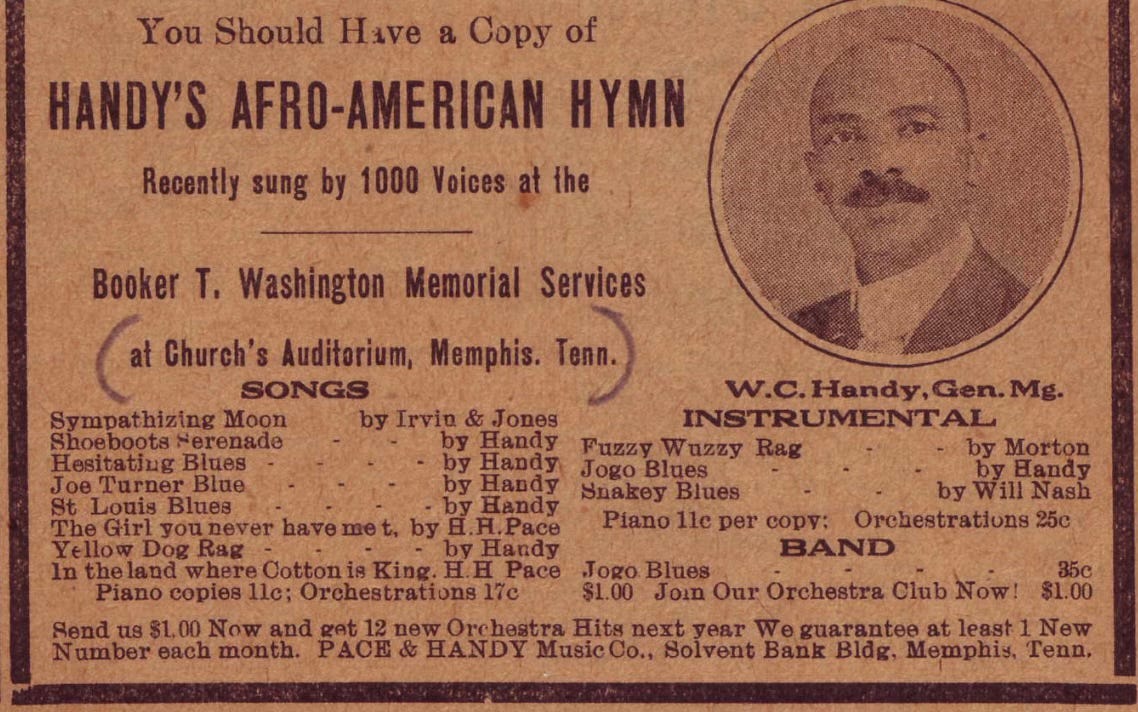

A couple of years later, Handy published sheet music for the song that had become known as “Mr. Crump” and remained popular at his gigs. He renamed it “Memphis Blues” and saw it become a huge hit and money-maker–for a slick song plugger who’d swindled him out of the rights.

“Mr. Crump” became a Beale Street standard, remade many times, including by the great Frank Stokes, who must have bet a friend he could get the word “Presbyterian” on a blues record.

Undaunted, Handy set up a music company and became the most successful Black songwriter of the time, sampling what he heard on Beale Street corners and in its many saloons (as they’d predicted, the people barrelhoused anyhow) to build hits like “St. Louis Blues” and “Beale Street Blues” on which he lived for the remainder of his years.

But Handy had to leave this creative environment due to the climate of terror around him. Crump had resigned the mayor’s office in 1915 thanks to an ouster suit against him, only to assume an even deeper, unelected role as machine boss behind the scenes.

In March of 1917, Handy published his “Beale Street Blues,” an ode to life on the boulevard that contains the phrase, “I’d rather be there than any place I know, it’s gonna take a sergeant for to make me go.”

Two months later, a black man named Ell Persons was accused of murdering a 15-year-old white girl. A planned lynching of Persons took place, with local media having spread the word beforehand and several law officers in attendance among the mob of five thousand who watched Persons suffer. Handy recalled that someone threw Persons’ head into a crowd at Beale Street Park. At that point, though he’d rather be on Beale than any place he knew, it didn’t take a sergeant to make Handy go. He relocated to New York, setting up his company on Broadway.

Crump had a more personal connection with another group of artists, the Memphis Jug Band.

With the Boss at his most ostentatious, the Memphis Jug Band accompanied the Crump machine train excursions to Hot Springs for the annual spring meeting horse races. They sawed away at Crump’s favorite tune, “Margie,” as the downtown boys rolled dice, the boss famously grabbing the horn for one throw, tumbling out seven and clearing the cash from the floor, saying, “That’s the trouble, you don’t know when to quit.” No one faded the boss.

To my ear, the Memphis Jug Band recorded the earliest examples of the dangerously laidback beat that would become a staple of the 1960s Memphis sound, playing rhythm like they can’t really be bothered to keep time but never missing.

Lyrically, Will Shade gives an intense up close perspective of the underworld’s underbelly during the Crump regime. Black lives did not matter. They never call out Crump directly, but by portraying a darkest reality, albeit in the most joyful noise, the band preserved a terrifying history that otherwise went undocumented, that we could not without them know.

“Cocaine Habit Blues” was an old time traditional ditty even by the jug band’s 1930 release date. Coke had been legal and widely abused in Memphis since the 1880s. Coke parties and the weird chants that broke out were old lore, evidenced by the jug band name dropping Lehman’s drug store, a narcotic retailer off Beale since the early 1900s. Nevertheless, the line “if you don’t believe cocaine is good, ask Alma Rose that’s in the woods” evokes the devastation and cost of addiction in a way in which only the Memphis Jug Band could.

Their 1934 release “Oh Ambulance Man” is something else. Lead vocalist Hattie Hart, who also leads on “Cocaine Habit,” drops us into the middle of a strange and chilling story–she is already severely wounded and being transported through harrowing weather across dismal roads to nowhere, in an ambulance. Rather than the safety and security one might expect, Hattie warns the driver, gently and carefully lest she provoke worse, to be careful how he handles her jelly roll.

Will Shade later explained the historic basis of the story. Local mortuaries operated ambulances. Their owners received a fee for burying a dead pauper in the county field but seemingly not for a speedy delivery to a hospital. Shade said, “If you wasn’t dead, well they’d have two drivers in there and one driver take a needle and stick it in you, and you’d be dead before you reached the hospital. Come feel your pulse and say, ‘Aw, he’s dead, come on take him to the morgue.’ That’s the end of you. You automatically dead.”

The Memphis Jug Band gives many such examples of singing what can’t be said. But most of what they did was even harder, they threw genuine joy into the face of despair.

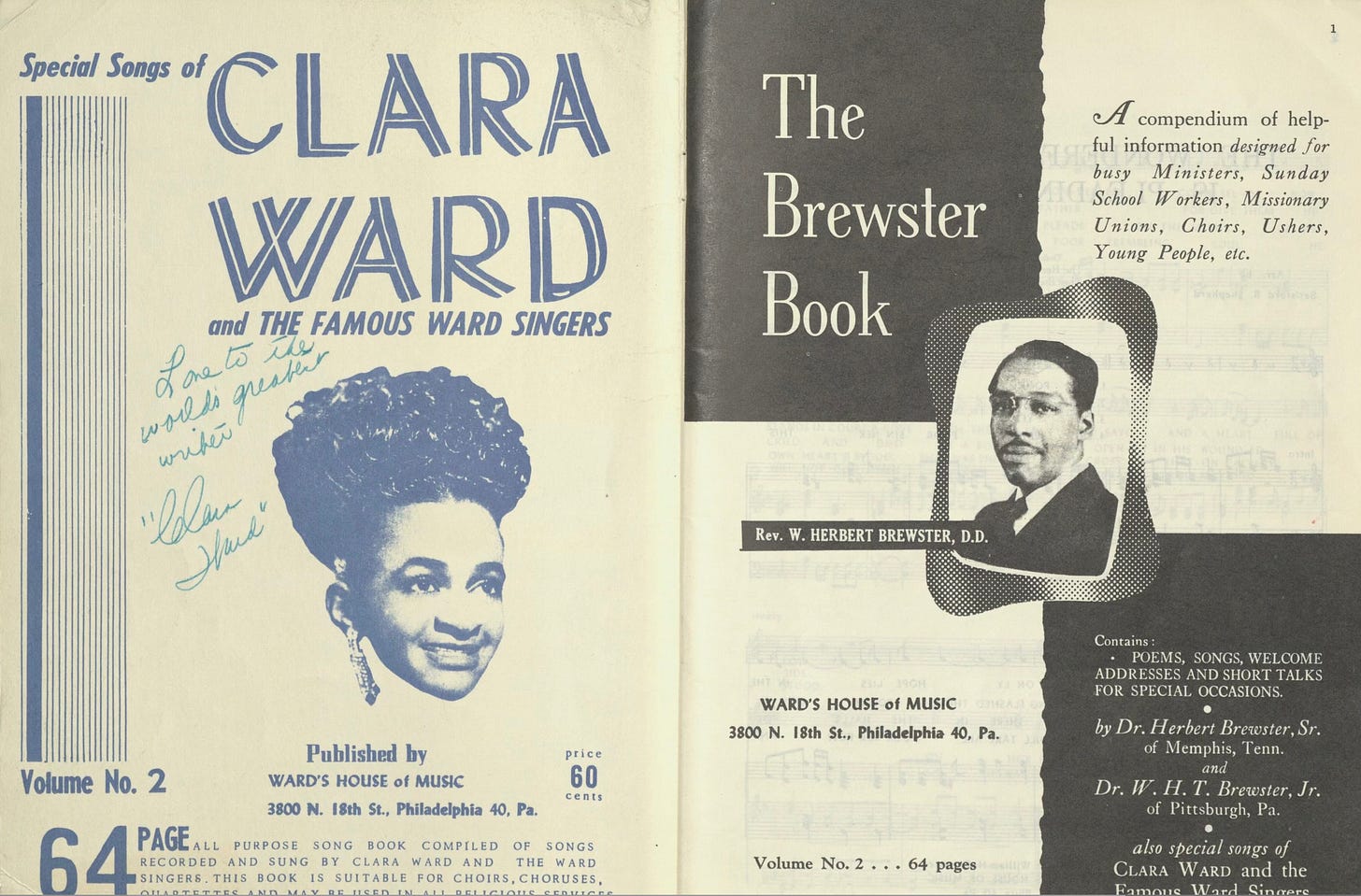

The lynching of Ell Persons in 1917 that had effectively moved W.C. Handy away from Beale Street also inspired a broad protest movement. The Memphis chapter of the NAACP rose from Persons’ ashes. A young minister from rural west Tennessee came to the city to participate and was inspired to truly monumental things. W. Herbert Brewster became a staunch political activist and prolific composer of hit gospel songs.

Brewster wrote his most enduring number, “Move On Up a Little Higher,” as a direct but coded response to Crump rule. It was he who told an interviewer, many years later, “There were things that were almost dangerous to say, but you could sing it.” A version of that sentiment made its way into the 2022 ELVIS biopic, with the Presley character mentally preparing for his socially conscious 1968 TV comeback special and musing, “A reverend once told me—when things are too dangerous to say, sing.”

“Move On Up” came about through Crump banishing black political leader Robert Church and terrorizing other black voting rights activists during the 1940 presidential campaign. Brewster com.posed the song to counteract racist dogma that black people were unequal to whites. As Crump said at the time, “You have a bunch of niggers teaching social equality, stirring up racial hatred. I am not going to stand for it. I’ve dealt with niggers all my life, and I know how to treat them. … This is Memphis.”

With Mahalia Jackson singing, “Move On Up A Little Higher” became the first black gospel recording to sell a million copies.

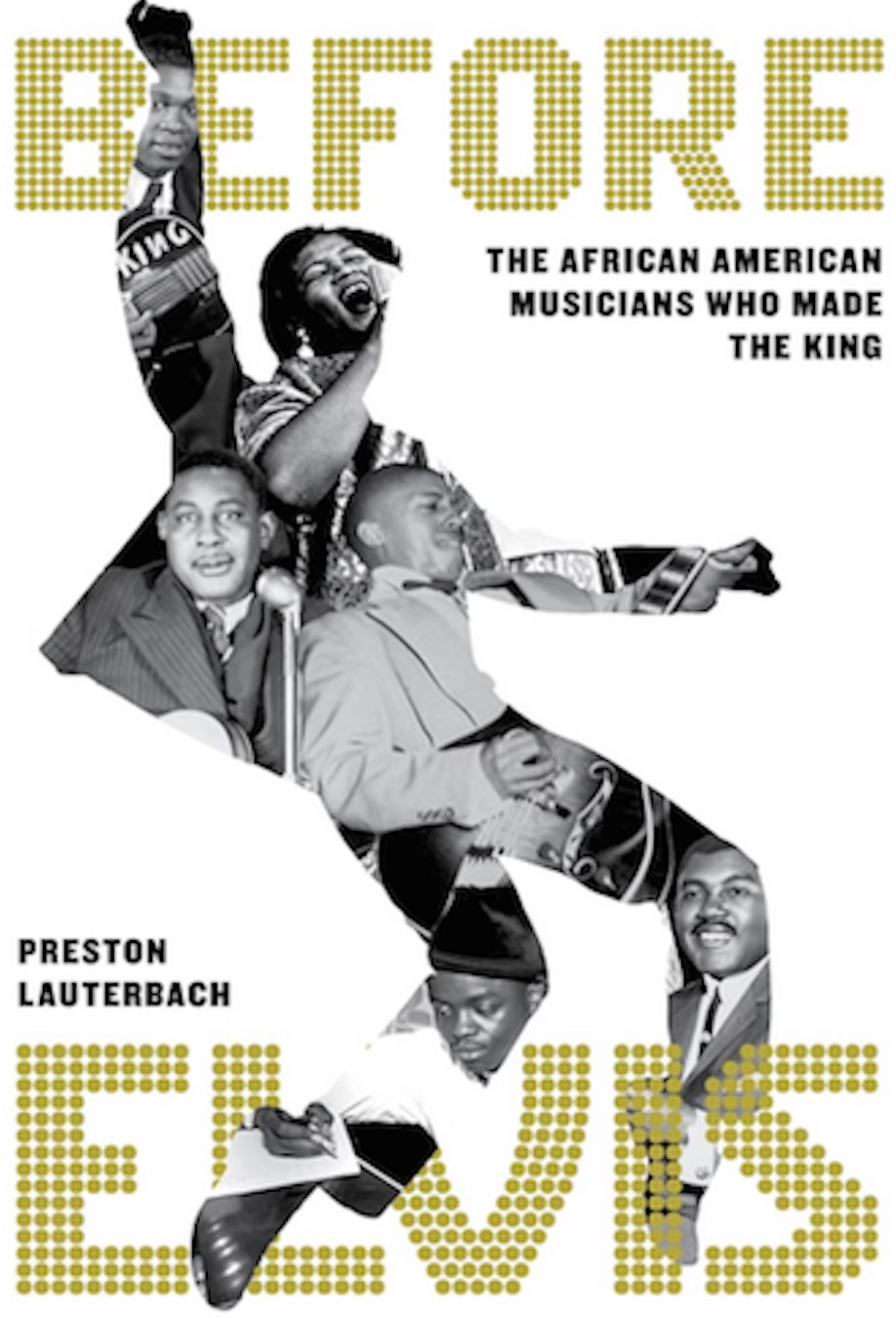

For a book length version of the Crump struggle for the soul of Memphis, I highly recommend Beale Street Dynasty, published in 2015, a book that, along with my new one will show how little my interests have changed in a decade. Dynasty winds to an end following the trauma of 1940, while Before Elvis picks up around 1948, when the Presley family moved from Tupelo, Mississippi to Memphis, the beginning of the end of the Crump regime.

Quiet as it’s kept, Elvis Presley took part in the most direct musical protest of the Crump machine. Crump had hired segregationist censor Lloyd T. Binford to purify the minds of the city, and Binford banned interracial seating at public events. Concerts and ballgames had either two separate showings for white or black audiences or separate seating. Lloyd T. Binford talked more racial shit than Martha Stewart at a celebrity roast.

He banned motion pictures from being shown in Memphis over the state Supreme Court’s opinion that a censor shouldn’t outlaw movies for racial reasons. “That doesn’t bother me a bit,” said Binford. “I will continue to ban pictures which I think are not to the public good, for both the white and negro races.” In 1948, he banned A Song is Born for featuring the integrated Benny Goodman Orchestra with vibraphonist Lionel Hampton. In 1950, Binford said that Imitation of Life, a 1934 movie, “illustrates some pretty strong things to negroes, that they are better than white people.” He banned it. He banned a Little Rascals spinoff movie called Curley for depicting Black and White schoolchildren sharing the same classroom. He banned Jack Benny movies for the comedian’s familiar relationship with sidekick Eddie “Rochester” Anderson. While some might reason that Buckwheat and Rochester don’t exactly challenge the status quo, Binford and Crump wanted no seed of integration or equality entering the city’s thoughts.

By 1953 the city had become, if I can plagiarize myself, the sort of furnace in which great people are forged. This condition prevailed undoubtedly due to the absence of any political or social opposition to Crump rule. The people had only culture. But damn, did they have it.

Dewey Phillips is an enigmatic figure. Though latter day white dudes like me geek out on him, black people who were around during Dewey’s time are a little eh about him. He almost certainly suffered from psychological distress as a World War Two combat veteran. He poetically recalled his experience at Hurtgen Forest, as an eighteen-year-old. He said that when he went into the trenches, the surroundings looked like a children’s storybook. At the end of the battle, not a tree remained standing.

In Memphis during the postwar years, Dewey deserves credit for desegregating the airwaves. His radio show mashed up black gospel and white hillbilly as if their musics and their people belonged together. He became a fan of Rev. Brewster’s and he encouraged white people to attend Brewster’s church services in order to hear the best of gospel singing. Elvis and many others answered the call.

I think that people generally understand that Elvis represented revolution, but I’m not so sure they know what he revolted against. Mr. Crump provides a whole new angle from which to appreciate Elvis’s rebellion. Fittingly, in October of 1954, three months after the release of Elvis’s first record, E.H. Crump died.

Though it feels gratifying that Boss Crump died just months after Elvis exploded onto the scene, the two don’t really have any more in common than a grand narrative sense of poetic justice. I don’t know if there’s a real silver lining to how Memphis culture blossomed during the Memphis dictatorship of Mr. Crump beyond the fact that it happened. Maybe that’s enough. For something else to happen, the possibility of something magnificent to occur in spite of what some feel as prohibitive darkness, is the best we’ve ever really done. If you’re feeling despair, I can’t say “Don’t” but I must say that alternatives exist.